Getting Down With The Kubernetes Krew

Some handy kubectl plugins found through the kubernetes plugin manager krew

In this post, after a brief intro to what krew actually is, I run through a dozen or so plugins I’ve installed using it which I find to be pretty handy time-savers. Hope you find at least one of them useful!

So, long time no post. I was resolved to posting more frequently in 2020 … and we’re at the end of February … so not so successfully then! Time to try to turn the tide …

On this occasion, I’ll be talking about krew. The focus of the post is some of the plugins that work for me, but there is a brief intro to what krew actually is if you’ve not heard about it before.

Notice how I managed to get this far without any mention of “top 10 krew plugins to help you devop harder”. That is a very deliberate avoidance of a clickbaity title. It’ll be interesting to see whether the article still gets picked up!

An intro to krew

In short, it’s a plugin manager for kubectl. Think brew or apt, but for your kubectl commands. Plugins have been a thing in Kubernetes since v1.12, and if you want to know a bit more about how they work then Ahmet Alp Balkan (creator of krew, as well as indispensable tools like kubectx & kubens) covers it really well here.

Installation instructions are straight-forward as you’d expect, and the basic usage is intuitive (I alias krew='kubectl krew'):

krew list- list your plugins installed through krew. If you only use krew to do this, this should be the same askubectl plugin listkrew search <string>- find plugins. Without<string>, all are listedkrew info <plugin>- more info about what a plugin does. I always check this to make sure a plugin isn’t going to do something dubious - it invariably contains a link to the source code. And let’s be honest, you’re basically running someone else’s bash on your PC with these pluginskrew install <plugin>- installs it - it can then be used throughkubectl <plugin>krew upgrade- upgrade your plugins

At time of writing, there are now ~70 plugins available through it. I feel like when I first started looking at krew in mid-2019, there were only a couple of dozen, so usage is clearly accelerating! 👍

On with the plugins themselves …

Viewing resources

First up in this section we have kubectl tail (usually kail). This is a handy plugin for tailing logs - it’s just nice and simple. There are a number of alternatives out there (I know some folks like Stern, which I’ve never got round to trying). The main feature I like is being able to target a deployment/service/ingress (e.g. kubectl tail --ing=mosstech) and be able to watch all the logs from the pods behind it, without necessarily needing to know how the resource has been labelled.

kubectl get-all does exactly what it says on the tin. They are not kidding - this really gets everything, as the plugin info page says. I’ve found this to be increasingly useful with our uptake of CustomResourceDefinition - i.e. where you may not be able to remember every type of object that exists in a namespace any more (usually because I want to delete stuff …). This plugin helps a lot with that:

[~ (⎈ |sandpit-prod:prometheus)]$ kubectl get-all -n=prometheus

NAME NAMESPACE AGE

configmap/prometheus-sandpit-rulefiles-0 prometheus 14d

endpoints/prometheus-operated prometheus 20d

persistentvolumeclaim/prometheus-storage-prometheus-sandpit-0 prometheus 20d

# [...]

prometheus.monitoring.coreos.com/sandpit prometheus 20d

prometheusrule.monitoring.coreos.com/prometheus-k8s-rules prometheus 14d

servicemonitor.monitoring.coreos.com/prometheus-operator prometheus 16d

poddisruptionbudget.policy/prometheus prometheus 20d

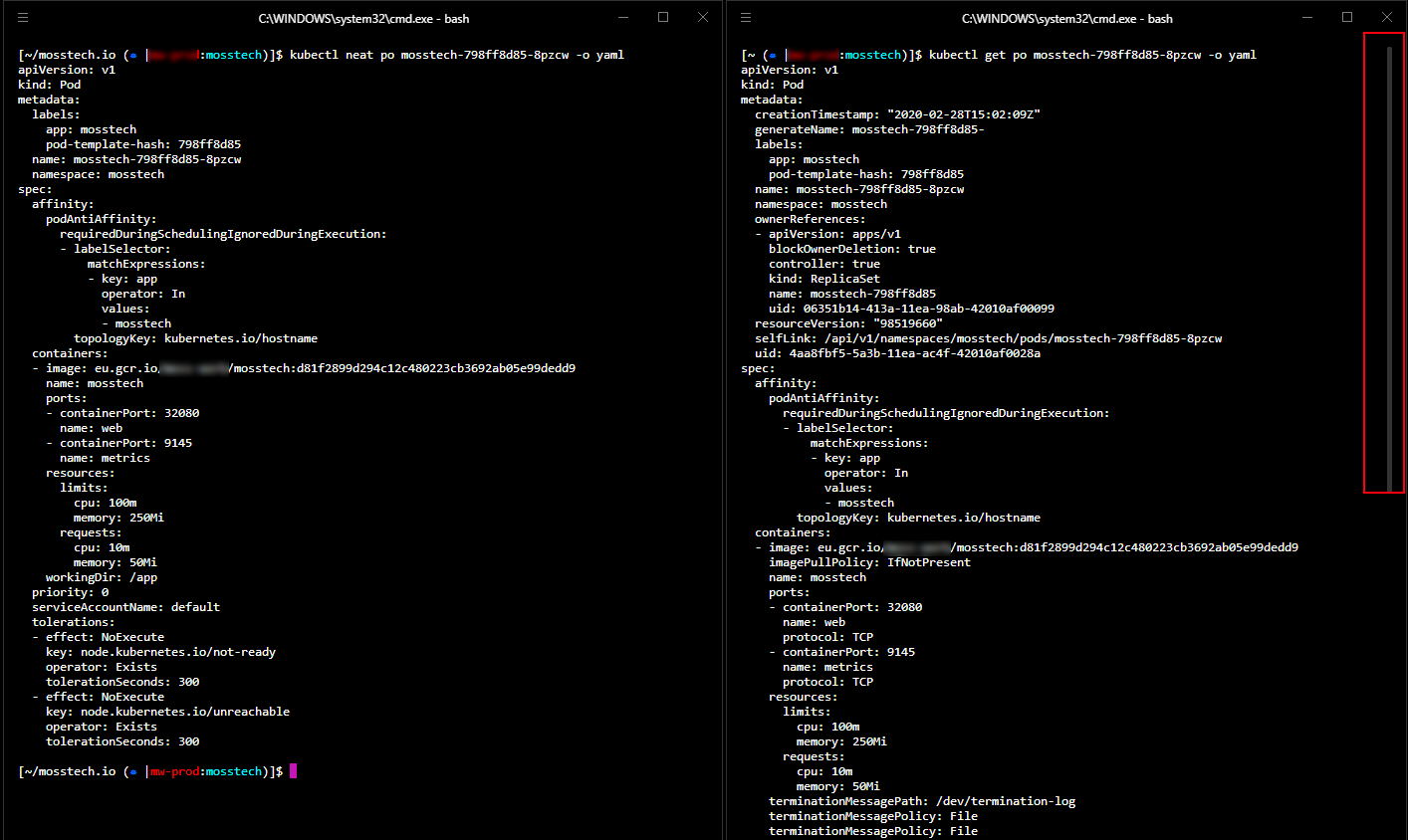

Almost the opposite is kubectl neat which, as the name sort-of-implies, neatens up verbose output. If you find your mind glazing over the system-injected annotations and such when get you get a pod’s details, this one might be for you - it strips the gumpf from kubectl get - for example:

Lastly for this section, are a couple of plugins that help visualise the relationship between a resource and other things in the cluster. kubectl pod-dive is good if you want to know what surrounds a particular pod, e.g.

[~ (⎈ |sandpit-prod:prometheus)]$ k pod-dive prometheus-sandpit-0

[node] gke-sandpit-prod-np-0-947e5a45-84zk [ready]

[namespace] ├─┬ prometheus

[type] │ └─┬ statefulset

[workload] │ └─┬ prometheus-sandpit [2 replicas]

[pod] │ └─┬ prometheus-sandpit-0 [running]

[containers] │ ├── prometheus [228 restarts]

│ ├── prometheus-config-reloader [0 restarts]

│ └── rules-configmap-reloader [0 restarts]

...

[siblings] ├── grafana-0

├── nginx-ingress-controller-85744dcf89-nswr9

├── fluentd-gcp-v3.1.1-bzh54

├── heapster-v1.6.1-5b6bf6cc74-cnnlh

├── kube-proxy-gke-sandpit-prod-np-0-947e5a45-84zk

├── prometheus-to-sd-cjkwx

├── node-exporter-7ml5r

WAITING:

prometheus crashloopbackoff (Back-off 5m0s restarting failed container=prometheus pod=prometheus-sandpit-0_prometheus)

TERMINATION:

prometheus error (code 1)

Somewhat similarly, kubectl tree shows the hierarchy for a particular resource - especially useful when working with CustomResourceDefinition. For example, here’s a view from my failing Prometheus pods (installed using the prometheus CoreOS operator):

[~ (⎈ |sandpit-prod:prometheus)]$ kubectl tree prometheus sandpit

NAMESPACE NAME READY REASON AGE

prometheus Prometheus/sandpit - 20d

prometheus ├─ConfigMap/prometheus-sandpit-rulefiles-0 - 14d

prometheus ├─Secret/prometheus-sandpit - 20d

prometheus ├─Service/prometheus-operated - 20d

prometheus └─StatefulSet/prometheus-sandpit - 20d

prometheus ├─ControllerRevision/prometheus-sandpit-6f6fcd787b - 20d

prometheus ├─Pod/prometheus-sandpit-0 False ContainersNotReady 29h

prometheus └─Pod/prometheus-sandpit-1 False ContainersNotReady 3h

Resource usage

There are a whole bunch of plugins in this area - I’ve picked out a couple that I think do a bit more than is easily achieved with some kubectl-foo. Some of these were particularly helpful when trying to squeeze more out of my tiny ‘home’ GKE cluster.

First, kubectl resource-capacity offers a nice and simple view for an overall cluster usage:

NODE CPU REQUESTS CPU LIMITS MEMORY REQUESTS MEMORY LIMITS

* 1136m (60%) 5795m (308%) 3147Mi (59%) 10983Mi (208%)

gke-sandpit-prod-np-0-3be8d635-6s5n 694m (73%) 3406m (362%) 1812Mi (68%) 5774Mi (218%)

gke-sandpit-prod-np-0-947e5a45-84zk 442m (47%) 2389m (254%) 1335Mi (50%) 5209Mi (197%)

Occasionally, info about disk utilisation is useful, and not super-obvious from other sources (like kubectl get) … enter kubectl df-pv:

PVC NAMESPACE POD SIZE USED AVAILABLE PERCENTUSED IUSED IFREE PERCENTIUSED

prometheus-storage-sandpit-1 prometheus prometheus-sandpit-1 21003583488 541843456 20444962816 2.58 3729 1306991 0.28

grafana-data-grafana-1 grafana grafana-1 1023303680 3493888 1003032576 0.34 23 65513 0.04

prometheus-storage-sandpit-0 prometheus prometheus-sandpit-0 21003583488 533467136 20453339136 2.54 3744 1306976 0.29

grafana-data-grafana-0 grafana grafana-0 1023303680 80232448 926294016 7.84 24 65512 0.04

And finally, kubectl view-allocations is handy for spotting pods without resource requests/limits (it’s not obvious from the capture below, but it highlights these in red):

Housekeeping

If you’re running a cluster that’s been around for a while, there are a few plugins that help you track down old or unused object:

kubectl deprecations- as the name suggests, warns you of objects in your cluster using older versions of objects. On my home setup, it was pretty good at telling me about all the APIs I was using that I’d specified usingv1beta1for example 😄kubectl prune-unused configmaps --dry-runis a handy one - it wipes out (… in other words you should definitely run with--dry-runfirst …) unusedSecrets orConfigMaps. Great for clusters I use for experimentation - which often leads to trashing things that don’t work outkubectl outdatedis a very neat idea - it finds images that running older versions than what’s out there in public - you can see it in action below:

Note that as it needs to be able to connect to the registry anonymously, it can’t check things that are in my private GCR - but then again, they should have healthy CI/CD pipelines pushing out the latest image automatically. If you pull and re-tag images privately though (e.g. to run them through a vulnerability scanner) then this is a bit less useful to you (or at least, it is without some fiddling).

Security

I’ll be the first to admit I didn’t “get” the RBAC setup in Kubernetes straight away. Even though I feel like I now do, having a couple of plugins to visualise permissions I find really useful, especially at work where our setup is needfully more complex.

The first of these is kubectl access-matrix, which in an RBAC-enabled cluster (which you really, really should have by now) has two modes:

kubectl access-matrix [-n=namespace]displays a table showing what the current user can do against each resource type. With no namespace, it looks at the cluster scopekubectl access-matrix for <resource>displays, for a given resource (e.g.pod), which users/groups/serviceaccounts can perform which roles in which namespaces if applicable.

It is the latter I find particularly helpful in our PodSecurityPolicy-enabled, multi-tenant (i.e. permissions per namespace) cluster at work.

Related is kubectl who-can, which as the name suggests shows which subjects can perform what actions on which objects. For example, the following tests who can create a Service in the sandpit namespace:

[~ (⎈ |sandpit-prod:default)]$ kubectl who-can create services -n=sandpit

No subjects found with permissions to create services assigned through RoleBindings

CLUSTERROLEBINDING SUBJECT TYPE SA-NAMESPACE

cert-manager cert-manager ServiceAccount kube-system

cluster-admin system:masters Group

elastic-cluster-admin-binding some-sa@some-project.iam.[...] User

prometheus-operator prometheus-operator ServiceAccount prometheus

In a better policed cluster than my sandpit 😁 you’d expect to see something a bit tighter than this!

If you’re worried about the hardening of your pods and willing to trust the folks at kubesec.io, then kubectl kubesec-scan is quite interesting. Here’s some output from an old deployment I know still has some dodgy stuff in it 😜

[~ $ kubectl kubesec-scan deployment dodgy-app -n=dodgy

scanning deployment dodgy-app in namespace dodgy

kubesec.io score: -56

-----------------

Critical

1. containers[] .securityContext .capabilities .add | index("SYS_ADMIN")

CAP_SYS_ADMIN is the most privileged capability and should always be avoided

2. containers[] .securityContext .privileged == true

Privileged containers can allow almost completely unrestricted host access

-----------------

Advise1. containers[] .securityContext .runAsNonRoot == true

Force the running image to run as a non-root user to ensure least privilege

2. containers[] .securityContext .capabilities .drop

Reducing kernel capabilities available to a container limits its attack surface

3. containers[] .securityContext .readOnlyRootFilesystem == true

An immutable root filesystem can prevent malicious binaries being added to PATH and increase attack cost

4. containers[] .securityContext .runAsUser > 10000

Run as a high-UID user to avoid conflicts with the host's user table

5. containers[] .securityContext .capabilities .drop | index("ALL")

Drop all capabilities and add only those required to reduce syscall attack surface

And finally in this section, a quick one for the lazy / keyboard efficient - kubectl view-secret [<secret>] [<key>] [-all] - no need to base64 decode things - tedious!

Debugging

In the last section, I cover a few plugins that can help with debugging issues.

First up, another one for those who don’t like typing - kubectl iexec - simplifies the kubectl exec -it <pod> /bin/sh wrapper by offering an interactive menu to pick the pod (+ container) you want to exec onto. kubectl pod-shell does basically the same thing too.

Sometimes - hopefully rarely - you need to elevate privilege to get to the bottom of what’s going on. There are a few krew plugins that help with this process, assuming you have enough permissions to do so.

kubectl node-admin is scary - it spins up a privileged Pod with the host node mounted, effectively acting as a “remote onto nodes” container. It basically does this …

kubectl run node-admin -i -t --rm --restart=Never --image=debian:latest --overrides="${SPEC_JSON}"

… where SPEC_JSON built up with a whole load of scary privileges to do stuff). Powerful, if for some ungodly reason you need to get onto a node directly. kubectl node-shell does largely the same thing too (except with alpine, and no fancy node-picker).

kubectl spy (kubespy) is a handy little utility for spinning up a (privileged) pod that can attach to another pod for debugging purposes. There is also kubectl debug, but this needs the 1.16 alpha feature EphemeralContainers switched on, which I don’t have. kubectl spy looks a bit like this:

[~ (⎈ |sandpit-prod:mosstech)]$ kubectl spy mosstech-798ff8d85-4qfp5

loading spy pod...

If you don't see a command prompt, try pressing enter.

/ # ls -la

total 44

drwxr-xr-x 1 root root 4096 Feb 16 21:13 .

drwxr-xr-x 1 root root 4096 Feb 16 21:13 ..

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 0 Feb 16 21:13 .dockerenv

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 12288 Dec 23 19:21 bin

drwxr-xr-x 5 root root 360 Feb 16 21:13 dev

drwxr-xr-x 1 root root 4096 Feb 16 21:13 etc

drwxr-xr-x 2 nobody nogroup 4096 Dec 23 19:21 home

dr-xr-xr-x 230 root root 0 Feb 16 00:09 proc

drwx------ 1 root root 4096 Feb 16 21:13 root

dr-xr-xr-x 12 root root 0 Feb 16 00:08 sys

drwxrwxrwt 2 root root 4096 Dec 23 19:21 tmp

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 Dec 23 19:21 usr

drwxr-xr-x 4 root root 4096 Dec 23 19:21 var

/ # ps -ef

PID USER TIME COMMAND

1 101 0:00 nginx: master process nginx -g daemon off;

6 101 0:00 nginx: worker process

13 root 0:00 sh

19 root 0:00 ps -ef

Meanwhile, a new busybox pod is running:

[~ (⎈ |sandpit-prod:mosstech)]$ kubectl neat pods spy-5092 -o yaml

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

mosstech-798ff8d85-8pzcw 1/1 Running 0 45h

mosstech-798ff8d85-9vd47 1/1 Running 0 6d10h

spy-5092 1/1 Running 0 5m21s

And finally …

And, if you’ve made it this far, I’ve saved the best till last. Are you brave enough to try … kubectl snap!

For Avengers fans hopefully what this is going to do is obvious 😁 (It deletes half of … everything)

In reality, it is somewhat gentle - see recording below: